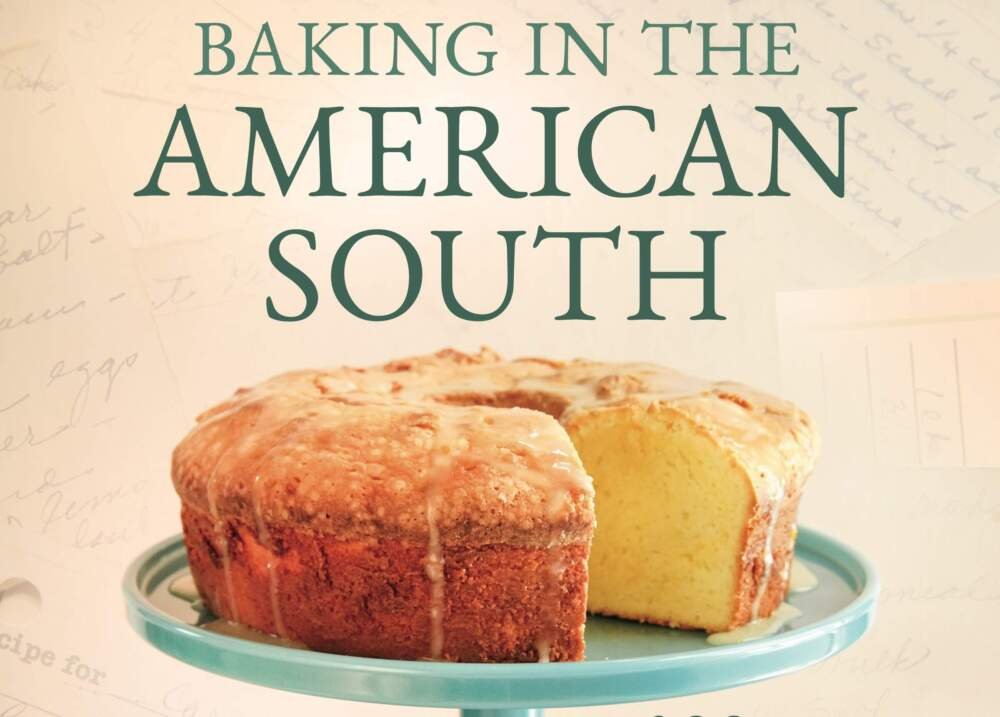

‘Baking in the American South’ shares the food and history of the region

Every now and then you find a new book that’s hard to put down. But perhaps that’s less expected when it’s a cookbook like chef Anne Byrn’s “Baking in the American South.”

The recipes are an eclectic mix of traditional Southern fare as simple as the buttermilk biscuit, as unexpected as the heavenly chocolate-tomato sheet cake, as elegant as the fig and lemon clafouti, and as comforting as Ma Hoyle’s double-crust blackberry cobbler. But what elevates the book are the backstories that accompany the food.

The book offers a history of the ingredients or a recipe’s connection to the Civil Rights Movement — like Zephyr White’s pecan pie, which might have influenced former President Lyndon Johnson’s decision to sign the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. And beautifully written essays mark the beginning of every chapter.

The 200 recipes from 14 states represent a tapestry of foods made by rich, poor, Black and white Southerners. Byrn says she contacted people from every state who shared their recipes in boarding houses, farms, cafeterias and synagogues.

In her research, Byrn found out cookbooks were published after the Civil War as a fundraising effort. These cookbooks contain recipes previously passed down only through word of mouth or family diaries.

“The cookbooks sold, and that funded war relief,” Byrn says. “But that also served as preservation because it preserved the 19th-century recipes of the South. And a lot of those recipes we still bake with today.”

Book excerpt: ‘Baking in the American South’

By Anne Byrn

Food has been perhaps the most positive element of our collective character, an inspiring symbol of reconciliation, healing, and union.

—JOHN EGERTON, SOUTHERN FOOD: AT HOME, ON THE ROAD, IN HISTORY (1993)

In the fall of 2021, traveling on a book tour through North Carolina, I stopped at the Country Bookshop in Southern Pines, where a woman from Ohio asked me, “What makes Southern baking so special?”

As a fifth-generation Southerner, I was at a loss for words. I naively wondered why the aroma of pound cake or the taste of soft, buttered yeast rolls needed explaining.

I looked to the audience for help. Hands were raised. It’s your mama’s cooking. It’s the biscuits. It’s the flour. It’s the people. In short, everyone from the South had an answer, but there was no definitive answer.

As I drove home to Nashville, through the Nantahalas and into the Great Smoky Mountains, driving past Knoxville, over the Cumberland Plateau, and back into the middle of Tennessee, the question stayed in my mind.

I have spent most of my life writing for and about Southerners. I recall after a stint in France studying pastry in Paris that I was homesick for Southern baking and would trade a fancy génoise for a warm slice of my mother’s pound cake any day.

But not until I dove into this book did I truly appreciate the deep baking legacy Southerners take for granted. It is quite possibly the first and finest style of baking America has ever known.

Baking Out of Necessity

While other pockets of the country—New England, the Midwest, and California—have their own regional baking styles, the South, which is about the size of Western Europe, has created more than its share of America’s best-loved recipes. Our cornbreads, biscuits, rolls, puddings, pies, cakes, and cookies with unique names, flavors, and stories create a deeply textured mosaic.

Without the number of commercial bakeries found in the urban Northeast, home baking in the South was out of necessity and used what the land provided. Take peach cobbler. If you’ve traveled to the South, you’ve witnessed the romantic affection we have for it and how it is a sacred rite of summer. You choose fragrant peaches to peel while juices run down your wrist and onto your arm, and you toss the slices with sugar, layer them in pastry, and bake a panful to feed a family, with scoops of vanilla ice cream, all season until next summer, when you do it all over again.

Peach cobbler was born from the profusion of ripe peaches that fell from the trees. The soft wheat ground into pastry flour had been planted in the fall and was harvested in spring before the heat and bugs set in. It had flavors of honeysuckle, vanilla, and faint black pepper. And in the years when wheat didn’t grow, you simply didn’t have wheat flour or peach cobbler.

Land and climate in the South differ from the rest of America. Sandy Gulf coastlines, snaky bayous, black-soiled farmland, lush river deltas, family farms where fig trees grow as tall as houses, and mountains encircled in a smoky blue haze define our land.

The South is different even in the way it smells:

the honeysuckle that weaves around a picket fence post and the fat blackberries or dewberries, full of chiggers and rattlers, growing wild along a hot and dusty Mississippi road. Here grand Georgia pecan trees on family land outlive their owners. satsuma, hickory, or pear trees dot back- yards. It’s as if the trees, fields, flowers, fruits, and vegetables etched into the Southern psyche have crept into everything we bake.

In comparison to other regions of the country, the South was an agrarian society where cooks lived far apart but were close to the land and fed those who worked it. The region was prone to storms and used to drought and all the vagaries of weather over which people had no control. It’s all the more reason Southerners have baked for others at quiltings, barn raisings, church dinners, political rallies, funerals, and celebrations of farm planting and harvest.

A ready supply of trees to fell for wood to stoke wood- stoves not only allowed cheap fuel but introduced the South to a biscuit we can never forget. Daufuskie Island author Sallie Ann Robinson recalled in her 2003 book, Gullah Home Cooking the Daufuskie Way, that, as a girl growing up off the coast of South Carolina, she would head home and light the woodstove so it would be nice and hot for her mother to bake biscuits. “Momma made it look so easy as she made the dough and rolled it out on the table. . . . She’d reach for one of the jelly jars that we drank from, then let me press it down into the quarter- inch dough to cut out the biscuits.”

A Story of Preservation and Art

Learning to bake a layer cake, ice it neatly, and sell it out of your home kitchen or at the beauty parlor paid some bills. When times were hard, cooks took in boarders in upstairs bedrooms and rolled out buttermilk biscuits each morning for the breakfast table. Struggling Southerners again looked to the land and the recipes they knew, and baking proved to be a currency outlasting Confederate money.

When Mother Nature didn’t cooperate, the South became an inventive no-waste region, baking pies of oats instead of pecans and flavoring with vinegar in lieu of lemon juice. Grandmothers baked layer cakes by measuring flour with a chipped teacup. Mothers taught their daughters how to bake cornbread with yellow cornmeal or white, with or without sugar, and these methods became as sacred as the Bible.

“Virtually everyone in the rural area where I was from would have had a milk cow. We milked that cow every day and churned our own butter. It was like life on Little House on the Prairie. You had to be self-sufficient,” says country ham king Allan Benton.

At the same time that baking in the North was influenced by factory innovation and commercial baking, Southern recipes became preserved in memory, written in diaries, or simply ripped off the box of baking powder. Cookbooks were published by charitable groups such as the Ladies’ Southern Relief Association, whose members fed, clothed, and sent money to the needy and wrote down recipes for fundraising cook- books, in the process preserving the classic recipes of the nineteenth-century South that we still use today.

Recipes became hyper-regional because their people were.

But what we bake isn’t always defined by state lines. It might be geography—the flow of the Cumberland, Chattahoochee, or Apalachicola Rivers; the plateaus and valleys; the Tidewater; the Bluegrass; or the stark isolation of the mountains—that informs the cake we bake. If you drive from western Georgia into eastern Alabama, you gain an hour in time, but the Lane Cake and the “lemon cheese” layer cake recipes, beloved in both states one hundred years after they were first created, know no time zones and are still baked each Christmas.

A Complicated South

Outsiders may imagine the South as a white-columned Tara from Gone with the Wind, but, in truth, the South was largely poor. The people of Florida’s turpentine camps, sawmills, and citrus groves existed on cornbread smothered in molasses. We have sweetened our food with sorghum molasses, cane syrup, the elusive sourwood honey found in higher elevations, maple syrup tapped from trees in West Virginia, or coveted white sugar, which was locked up in colonial kitchens and later blockaded and inaccessible during the Civil War.

Sugar, essential to Southern baking, is complicated. So is the South. Along with cotton and rice, sugarcane created an economy dependent on slavery, and the enslaved cooks provided the labor that made the biscuits, cornbread, pies, and cakes we still bake today.

From West Africa, enslaved Black cooks brought their knowledge of frying, preparing grains, stewing greens, and integrating heat and spice. And while buttermilk pound cake, rice pudding, and sweet potato pie might evoke nostalgic memories for some, for others who did not bake out of joy, they may mean something else altogether.

Pound cakes—fixtures at church suppers, funerals, and christenings—have built churches and funded schools. They also had a close relationship with the Civil Rights Movement. Georgia Gilmore and other Black women baked golden loaves of pound cake to raise money for alternative transportation as part of the 1956 bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama.

Pecan pie was the specialty of President Lyndon Johnson’s longtime cook, Zephyr Wright, of Marshall, Texas, who followed him from the ranch to the White House. She couldn’t board the same flights as the First Family because of Jim Crow laws. In making the long car drive to Washington, DC, she couldn’t find adequate rest stops and restaurants along the segregated route. She told the president about it, which Johnson said influenced his signing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Migration and Change

Although Southern recipes have retained their character, they weren’t frozen in time. Migration brought waves of immigrants through New York and the southern ports of Baltimore, Charleston, and New Orleans. They arrived to build the life they wanted—French Huguenots, English Quakers, Scots, Irish, Acadians, Italians, Swiss, Germans, and Jews from both Sephardic countries and Central and Eastern Europe. The enslaved from Africa and the Caribbean came because they were forced to.

Railroads built to shuttle cotton to market strung together towns like a mother’s strand of pearls and changed what we baked forever. A small town in southern Kentucky was a hub connecting rail lines north and south, allowing imported bananas to travel from docks in New Orleans and Mobile clear up to New York and Philadelphia, which might explain why there are so many banana pudding recipes embedded in Kentucky cookbooks. Because of railroads, a bakery and a beloved hundred-year-old recipe for a spiced cookie came to remote Demopolis, Alabama. Railroads made Key lime pie famous and turned nameless places into thriving towns with tearooms and boardinghouses, employing legions of good cooks who could bake blackberry cobbler and fry chicken.

The Recipes and the People

Southern baking, just like French cooking or Italian, has foundational recipes that stand the test of time—custard, angel food cake, pound cake, lemon curd, piecrust, biscuits, even cornbread. And the years have been good to Southern baking, allowing it to grow along the way and blossom into a style unlike any other.

The recipes in this book come from fourteen states—Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Like Hummingbird Cake or Black Bottom Pie, some of these recipes are famous. Others, like Cantaloupe Cream Pie or Heavenly Chocolate-Tomato Sheet Cake, you may never have heard of. You will absolutely want to bake Thomasville Cheese Biscuits or Maggie Cox’s Warm Chocolate Meringue Pie during the week. Other recipes, like Elizabeth Terry’s Sherry Trifle or Phila Hach’s Salt-Rising Bread, are so over-the-top, you’ll save them for a weekend project.

The sources for these recipes are as diverse as the recipes themselves. They come from department stores, school cafeterias, tearooms, boardinghouses, historic homes, cookbooks, churches, synagogues, restaurants, farms, mills, pastry shops, catering kitchens, home kitchens, and even the White House. I’ve included some of my own family’s favorites, too, which were baked by my aunt and grandmother as well as my mother, a wonderful cook, and I’ve perfected them over the years.

Recipes are my way of introducing you to the bakers of the South, from the nationally famous chef Edna Lewis and the self-made restaurant critic and businessman Duncan Hines to lesser-known but important cooks like Kentucky’s Atholene Peyton, a Black home economist who was ahead of her time, and Malinda Russell, who wrote one of the earliest Black-authored cookbooks, to locally acclaimed bakers like Pat Lodge, who was famous for her simple spoon rolls, and Alice Jo Lane Giddens, who made the crispiest sugar cookies ever. Prior to the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, many of these “ladies who baked” were referred to by their husband’s initials. And many Black cooks who created these recipes were not credited at all. They are now.

From sizzling cornbread—the South’s true daily bread, because corn grew everywhere—to light and flaky biscuits, to quick breads and batter cakes as well as fried breads that assuage hunger, to yeasty rolls and loaves, to puddings both baked and stirred on the stovetop, to pies large and small, to cakes that make every occasion special, to cookies, sweet and buttery—these are the recipes that tell the story of Southern baking. They open a window into the past and speak of the people who made them, where they came from, and why.

These recipes talk about the land and the harvest, when there was plenty and when there was not. They talk about the weather, adapting to it, dealing with it, and surviving it. They talk of isolation. They reveal discrimination and assimilation. They show the joy found in reunions, homecomings, and holidays. They know the unwritten code of borrowing one cup of sugar and returning two. And they are delicious.

Thirty years ago, when I was living in the Midlands of England, my new friends wanted me to bake American brownies and layer cakes, but my recipes wouldn’t work to my satisfaction with the hard and gritty British flour. I wrote to White Lily, which at the time was still based in Knoxville, asking if they might ship me a sack and include a bill. I didn’t expect to get a reply, much less flour. But a few weeks later, a box arrived with twenty pounds of White Lily all-purpose flour.

Today, you don’t have to live in the South to access Southern ingredients. You can order Southern flour and cornmeal online. And you can absolutely make these recipes with ordinary supermarket ingredients, no matter where you live. In the best tradition of the South, use what you have.

*

This book is my attempt to address a question many people outside the South might like to ask. My answer is that when you bake a banana pudding with a tall browned meringue, a rich chocolate pound cake re-created from memory, and sweet potato biscuits filled with shaved Kentucky ham, you will understand what makes Southern baking so special.

—Anne Byrn, Nashville, Tennessee, April 2023

Gottlieb’s Chocolate Chewies. (Courtesy of Rinne Allen)

Gottlieb’s Chocolate Chewies. (Courtesy of Rinne Allen)

Gottlieb’s Chocolate Chewies

Mrs. Collins’ Sweet Potato Cake. (Courtesy of Rinne Allen)

Mrs. Collins’ Sweet Potato Cake. (Courtesy of Rinne Allen)

Mrs. Collins’ Sweet Potato Cake

George Washington Carver’s sliced sweet potato pie. (Courtesy of Rinne Allen)

George Washington Carver’s sliced sweet potato pie. (Courtesy of Rinne Allen)

George Washington Carver’s Sliced Sweet Potato Pie

Blackberry jam cake. (Courtesy of Rinne Allen)

Blackberry jam cake. (Courtesy of Rinne Allen)

Blackberry Jam Cake

Taken from Baking in the American South: 200 Recipes and Their Untold Stories by Anne Byrn. Copyright © 2024 by Anne Byrn. Photographs © 2024 by Rinne Allen. Used by permission of Harper Celebrate.